| WORLD VOICES THE LANGUAGE

RAVEN GAVE US

BY JOHN E. SMELCER |

Contents

Home World

Voices Home |

Introduction The

poems assembled here are among the rarest examples of a culture's

literature in existence. They come from one of the world's most

endangered languages, one which had no written form even a generation

ago, a language—so our mythology says—was given to us by Raven. Ahtna

is one of twenty linguistically distinct indigenous languages in Alaska

(now, nineteen since the last native speaker of Eyak recently passed

away). Ahtna is a member of the broader Dine' language family, which

includes Navajo. The Native languages of Alaska fall into several

encompassing groups: Yupik and Inupiaq (popularly labeled “Eskimo”),

the southeast languages (Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Eyak), Alutiiq

(Aleut and Sugpiat languages), and thirteen interior Athabaskan

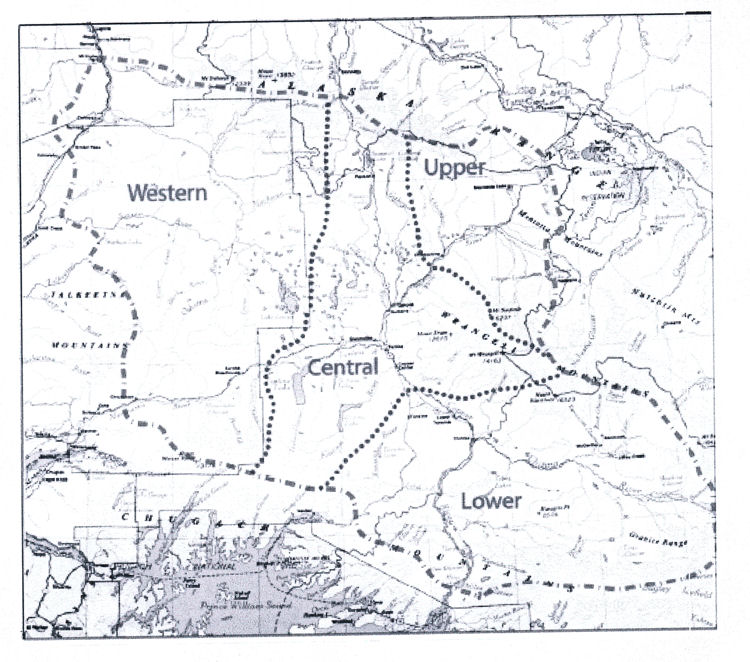

languages—Ahtna being among them. Ahtna has four regional dialects (see

map below). My grandmother's older sister, Morrie Secondchief, who

lived in Mendeltna (literally, “Between Two Lakes;” men

sometimes ben is our word for lake; notice the root word in

Mentasta below), was the last speaker of our Western dialect.  In

1980, linguists at the University of Alaska Fairbanks determined that

there were some 120 speakers of our language. By 1990, that number had

fallen to about 60. By 2000, fewer than 50 survived. Today, the total

number of speakers is less than 30. Aside from myself, Ruth Johns of

Copper Center, the widow of our last traditional chief, Harry Johns,

was the only other Ahtna speaker who could fluently write in our

language (she spoke our central dialect). I participated in the

potlatch ceremony honoring him as chief. I also attended Harry's

funeral potlatch a few years later. Ruth died shortly thereafter,

leaving me as the last person who can read and write in Ahtna. I

remember talking to her at the Alaska Native Medical Center just before

her death. Within

the next decade, because I am by far the youngest speaker of Ahtna

still alive, I will most likely be the last speaker on earth—a grave

and awesome responsibility. Indeed, the late Carl Sagan once wrote of

my unenviable duty to preserve my language, “no other American poet

shares such a heavy cultural burden.” Throughout

much of the 1980s, I was an undergraduate in anthropology,

archaeology, linguistics, English, and education at the University of

Alaska Fairbanks. Ahtna Native Corporation supported my education with

scholarships for much of that time, also supporting me during my

postgraduate studies in comparative literature in the early 1990s. My

area of concentration was Alaska Native cultures and languages. I

studied linguistics under Lawrence Kaplan and Michael Krauss, and had

discussions about Ahtna with James Kari, who had worked with many of my

relatives in the previous decade. As

the son of an Ahtna Athabaskan father, I took an immediate interest in

our language. I was taught at first by my full-blood Indian

grandmother, Mary Smelcer-Wood, and her sister, Morrie Secondchief. I

called them both grandmothers as is our custom. While raised in the

same abandoned village, Mary had only a rudimentary vocabulary, while

Morrie was fluent. I used to take Morrie blueberry picking and caribou

hunting with me. Her husband, Joseph Secondchief, who died when he was

ninety, stubbornly never learned to speak English. The only word he

knew was “porcupine.” He loved the taste of porcupine, and I used to

hunt them for him once he was too old. It was he who taught me the

secret of quartering the sharp-quilled animal, which we call nuuni

[pronounced: new-nee] in our language. He was among the last of his

generation.

For

much of the 1980s, I traveled to our villages meeting elders to

continue the arduous task of learning our language. My uncle Herbert

Smelcer, a well known tribal leader, made the initial contacts and

introductions on my behalf, since most of the elders did not know my

father. Each summer, I traveled to villages as far away as Mentasta and

Chitina. I also traveled around Alaska collecting traditional myths and

stories about boarding schools from elders in such remote places as

Minto and Nulato and the Eskimo communities of Point Barrow and

Kaktovik, also called Barter Island. The myths eventually ended up in

my book, The Raven and the Totem, for which the late

mythologist Joseph Campbell generously provided a foreword. Thanks

to my father's mother, my grandmother, who gifted me some of her

shares, I have been a shareholder of Ahtna Native Corporation and

Tazlina Village Traditional Council since 1995. When my grandmother

died in 2004, of all her children, grandchildren, and

great-grandchildren, she left me her shares in our Native Corporation,

which in Alaska, substitutes for the reservation system in the Lower-48. As

I said previously, my uncle Herbert Smelcer was one of Alaska's most

influential Native leaders. He was involved in the Alaska Native Land

Claims Settlement in the 1970s, signing Indian Rights legislation with

President Jimmy Carter. For all of Ahtna Native Corporation's

existence, he served on the Board of Directors and was at one time

president. For all my adult life, Herb instructed me with great

patience and intensity in the ways of our culture, as is the custom for

uncles. We hunted together and maintained our family's subsistence

fish-wheel in Tazlina. A fish-wheel is an ingenious device designed to

rotate by river current, scooping up unwary salmon as they spawn

upriver. He told me often how much he loved me. When Uncle Herb also

died in 2004, I spoke to a packed audience at his funeral service held

at the Alaska Native Heritage Center in Anchorage. I wrote both his and

his mother's obituary. I cannot escape who I am. Like you, I am the

product of the people who raised me and loved me and instructed me, and

of a place and of a culture. I can be no other. In

the summer and fall of 1995, after leaving the University of Alaska

where I co-directed the fledgling Alaska Native Studies program, I was

hired by Ahtna, Inc. to conduct archaeological fieldwork around

Glennallen, along Klutina River, and throughout the region near the

confluence of the Kotsina, Copper, and Chitina Rivers, where Ahtna had

sold timber rights, eventually publishing a book on my findings. By

late winter, I was tribally appointed the executive director of the

Ahtna Heritage Foundation. For the next three years, until the summer

of 1998, I was instructed by every living elder in the Copper River

valley who spoke any degree of Ahtna. Every two weeks—even at fifty and

sixty below zero—elders came to my office in Glennallen to

enthusiastically and meticulously teach me every word in our language.

That's nearly 100 workshops! The end result was that I would become the

living repository of our language. Whereas one elder may have

remembered fifty or a hundred words, another could recall only a few

place names or the names of some plants or animals. Eventually, I

became the one person who was taught—collectively—every single word in

our living cultural memory. I used my education and energies to produce

not only a dictionary, but also curriculum materials, a bilingual

children's picture book, language posters, and a series of oral history

collections. The Ahtna Noun Dictionary and Pronunciation Guide

was published in May of 1998, and In the Shadows of Mountains

(foreword by Pulitzer Prize winner Gary Snyder) contains every known

myth in our culture. While executive director, I was invited to speak

to other Alaska Native village organizations and reservations across

the nation about language preservation. In late 1998, I was nominated

for the Alaska Governor's Award for my work on the preservation of

Alaska Native cultures and languages. It

is worth noting that The Ahtna Noun Dictionary was incomplete.

Supporting grants stipulated that a product had to be delivered by a

deadline, and so I published what I had at the time. I still have over

100 pages of handwritten notes on yellow legal pads, which were not

included. It has always remained my plan to expand the dictionary. From 2004 until the summer of 2008, I worked with the village elders of Chenega, an island village in Prince William Sound, to document their endangered Alutiiq language and culture. With their help, I have completed about half the dictionary. I am now one of only about a dozen or more people who can speak and write in their dialect. Aside from a successful poster series and a DVD series, two important nonfiction books were published from those efforts: We are the Land, We are the Sea and The Day That Cries Forever, which was later adapted into a play. The

bilingual poems in this collection represent the only literature in the

Ahtna language extant. It is the greatest honor of my life that both

the Ahtna people and the villagers of Chenega entrusted me with their

most precious resource: the very language in which they express their

existence within the universe. |